Short notes on a long form, after a koodiyattam performance

- What happens to a complex art form outside its space of performance?

- Koodiyattam, outside the koothampalam inside the temple. There are measurable physical losses: The acoustical properties of the drums are richer, more resonant in the temple theatres owing to the high wooden roof of the building and canopied wooden ceiling above the roofed stage. There is a loss of 'feel'. These may be recovered by watching a performance in the koothampalam. Other losses may not.

- Koodiyattam – 'combined acting'. Two thousand years old or less, it is a form of Sanskrit theatre traditionally performed in Hindu temples in Kerala.

- A modern koodiyattam artist must ask himself questions older koodiyattam artists did not ask themselves. (‘The contemporary artist … [will have to] overcome challenges with an awareness of them, which … [his] ancestors did unknowingly.’ Margi Madhu.)

- Can the poetic modes of expression we find in Sanskrit drama be presented on stage? Can we express the various literary embellishments – alankara (simile), upama (metaphor), utpreksha (exaggeration), atishayokti (elaboration), varnana (multiple meanings), slesha (a word or a phrase which can be interpreted in two ways, especially one having one meaning that is indelicate), dhvani (suggestion, intended/unintended)?

- But what do we mean by expression?

- Each traditional art form has a language. There are gestures in performance or tones in music that indicate moods. An untrained eye or ear may mistake eroticism for sadness, happiness for peace. There are people who understand the language of Hindustani classical music. There are many such people.

- There is a real problem of method in understanding or responding correctly to a work after the rejection of transcendental authority. An art form like koodiyattam has been nurtured before this rejection but we receive it after this rejection.

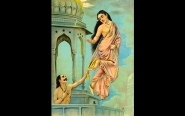

- Ritual formality marks the beginning of virtually every performance. On the actor's entrance I was struck by the make-up and costumes of the character. The face is not a mask. It is similar to kathakali at first sight.

- The actor gives off a feeling of tremendous weight. A presence. There is no trace of the appearance of the actor. If one comes back and Googles the performer, as I Googled Margi Madhu who enacted a gesture of Ravana's that evening, how slight the performer actually is. This is not because the actor appears large but because of the impression of great weight and gravity, not gravitas but a physical feeling of gravity – like being on Jupiter.

- The staging conventions involve symbolic gestures, exaggerated facial expressions and eye movements as well as stylized physical movements. The facial expressions are guided by the Natyashastra. The staging conventions are strict.

- There are people who understand the language of koodiyattam. There are a few such people.

- A person watching a koodiyattam performance in a city watches it knowing only the most rudimentary things about it. The form is complex and there is little material available to educate oneself about it.

- I know only rudimentary things about it – most of it gleaned from performances. Like trying to understand the rules of chess by watching game after game. The complexity of koodiyattam is comparable not to chess though, but to the Japanese game of Go.

- I do not worry about not knowing enough about koodiyattam. That is how I watched it. That is how most people today and almost everybody outside Kerala watches it.

- A single oil lamp stands downstage centre. The actors focus their attention in the direction of the lamp and often stand or sit relatively close to it. Two drummers sit behind the actors facing the spectators; one or two women sit on the floor stage right striking small metal cymbals. They are present throughout.

- There is an absence of scenery altogether.

- The flow of the action emphasises abbreviated story elements and acting rather than a linear plot with beginning, middle, and end. A one-act Sanskrit drama which takes half an hour to read takes many nights to perform. Performances in cities, about two hours long, will enact only one long action by a character.

- Is there a connection, not historical but in how we respond to it, between the imitation of an action in Greek tragedy and the enactment of an action over a long period of time in Koodiyattam? A lightness from the lack of psychologising together with great force.

- Most of the dramas used for Koodiyattam belong to the so-called Trivandrum Sanskrit Series – discovered in Travancore by T. Ganapati Saastri at the beginning of the twentieth century.

- If you do not like Kathak or Bharatnatyam or Kathakali or the other popular forms of Indian dance, this does not mean you will not like Koodiyattam.

- Vice-versa.

- If a performance follows koodiyattam, leave. You will be pitched into faster time – the absorption required by koodiyattam will not be present with kathak or kathakali. You will try to understand it.

- Leave. Don't Google form or performer. Try not to understand it. After time has passed, read these three lines by Walter Benjamin: 'Distraction and concentration form polar opposites which may be stated as follows: A man who concentrates before a work of art is absorbed by it. He enters into this work of art the way legend tells of the Chinese painter when he viewed his finished painting. In contrast, the distracted mass absorbs the work of art.'

- Go alone with nobody to rush or question you. Koodiyattam is a community form best watched alone, as I learnt that evening (by going alone) and on subsequent evenings (by not).

- Does cultural accumulation – culture itself – come to be with the bourgeoisie? (Or with civilisation Because money can buy the intellect with which you’d view a performance?

- To a person outside the temple, a person who isn't the Praneshacharya ? of the first half of Samskara, a person who has entered modernity, to such a person koodiyattam is no longer of cult significance. It is present as the heritage of India, that is – as culture.

- There is an aspect of both older art as well as modernist art which is acultural – older art has a cult value, modernist art acknowledges it is useless for community and wishes to be so for culture. Both get co-opted as culture.

- 'In Japan today, and for some time since the early part of the 20th century, Noh has been appropriated by the intelligentsia as a sign of personal refinement, hence the large number of students who study and learn to perform Noh in public recitals. We see nothing like "this phenomena" in koodiyattam. The closest the Indian public comes to replicating ... [this] is in various genres of Indian dance, "particular the bharatanatyam".' - Farley Richmond

- 'Other losses may not.' This must be acknowledged by any artist seeking to revive a form today. The revived dastangoi is popular but it is artificial. It is artificial because it has adopted – what must be – a revised form of the customs of dastangoi and has asked to be treated with respect and care simply because it was extinct and is being revived. The preservers are pleased but I am uncomfortable with such revivals which seek to bring back a dead form, with changes, rather than adopt what can be adopted from the dead form. (Ezra Pound on Sappho.) The respect given to a form of art should not have in it too strong an element of 'do not speak ill of the dead'.

- All that is revived must be revised.

- The dastangoi tries to create an aura.

- Koodiyattam has an aura. Created in part by its unbroken history, in part – in modern theatres – by the lamp and the drumming that precedes the performance. Destroyed in part by the modern theatre and the garlanding by dignitaries that succeeds the performance.

- The sound of drums starts and ends every performance.

- A dignitary starts (condescending introduction) and ends (garlanding) every performance.

- The question of reception may be intertwined with the question of preservation in the mind of the preserver of the old art form but it must not impede the reception of the art by the receiver who cannot truly receive it as heritage to be respected.

- Trying to understand impedes reception.

- In reception, one must not presume to understand. First accept completely the otherness of koodiyattam. Having accepted it, don't hold yourself responsible – use what you can of it.

- Slow forms can have two effects – they grip you or they don't at all. My few experiences with slow forms have been richer the slower they have been. There is a clarity about slow forms that is not necessarily lacking in fast forms but which we tend to miss in its excitement and distraction.

- The eyes, reddened in striking contrast with the face painted green, interest me the most, they absorb me, looking into them move from left to right is to move something in your chest from left to right.

- Yet how well could I see them that evening?

Anirudh Karnick was born, grew up and came to. He studied at and realised he'd prefer not to. He divides his time between Room 48 and Room 45 of a hostel in Delhi.

Note: Certain sections describing koodiyattam are edited portions from Farley Richmond’s paper presented at a conference in Amsterdam and available on his website:http://farleyrichmond.uga.edu/projects/index.htm