Tanya Mehta in conversation with Veeranganakumari Solanki reveals her process of creating a reality through the mythical portrayal of found images, self-portraits and created places through layers of imagery and meaning.

Veeranganakumari Solanki: Myth, magic, fantasy are things we grow up with. As we get older, we tend to argue these fantasies out of our minds with logic. You recreate these visions in your work. What is your earliest childhood memory that you have of this created world?

Tanya Mehta: My childhood was generously strewn with fantasy and imagination. A lot of it is owed to my parents who read to me and encouraged and nurtured this phantasmagorical streak in me. Besides the obvious tea parties with my stuffed toys and dolls and dancing around the room with my sister, sticks in our hands pretending we were fairies, my mother encouraged me to write stories that must have helped develop the larger, darker stories I tell now.

VS: As a child there were books we all read that let us create worlds in our minds and imagine ourselves a part of unknown universes. Were there any such books, movies or tales that particularly inspired you?

TM: So many, that it is almost impossible to recount them all. Particular favourites earlier on were Enid Blyton’s “The Wishing Tree” series, which still nostalgically sits on my book shelf today. I lived the books that were read to me in a detail that was almost eerily specific. What joy there was in those pages, what anxiety during the darkness of the first encounter with Bilbo and Gollum from Tolkien’s “The Hobbit”, the heartstopping passages of the near-encounters with the dragon, the constant play on darkness and light, relief and fear as each encounter was successfully scaled only to fall into another…

VS: The idea of image and communication (which you also studied at Goldsmiths) is also evident in your digital collages, which portray an immediate sense of mythical references. What stirs you to create spaces such as these?

TM: Ever since I was a child I felt there was a certain lack in the world we term “reality”. The here and now lacked a certain enigma, a certain magic. I grew fascinated with history, mythology, art, literature and music. I feel the subconscious is aware of, and holds, deeper truths to life and existence that are not always physical but exist nonetheless deep beneath our social obligations and reflections. I wanted to be able to explore these personal truths and, more importantly, use my art to find more universal ones. In turn, one man’s food is another man’s poison.

VS: Some of the images you use are immediately recognisable; yet, they attain an almost gothic aura in the context that you place them in. They are layered – often with references that one would not commonly associate with construct semiotic realities. By creating these works, which you refer to as realities of your own, you are, in a sense, making a mythical image a reality. Could you untangle this realism to better understand the myth or vice versa?

TM: In my mind, the two are entwined. Myth was probably once reality although perceived differently in the present of when it actually existed. The stories of these realities probably changed over the ages, slowly and subtly altering the events to give rise to myth. At each stage of it being passed on down in time, the myth existed in a different personal reality. Achilles was not always the fawned-after character played by Brad Pitt. In fact, there has been speculation that Achilles didn’t have his famous heel in Homer’s original, “The Odyssey”. It only got introduced in “The Achilleid”, written by Statius in the 1st century AD. All I’m doing now is trying to explore how such myths might be better relevant to a more contemporary day and age. ”The Modern Man, for example, represents a modern man: suited, powerful and wealthy but with no substance, a ghost of a human being with no soul or form. The myth of today is no longer a romantic one.

VS: The last layer that forms the surface of all your works is like an opaque sheet that marks the passage of time. There is an element present that confirms the creation of mythical narrations of real incidents – leaving the viewer questioning how much of what they see is real, leaving them believing what they want, leaving the rest of reality to myth.

TM: I see these scratch marks as a signature, kind of. As you have pointed out, they indicate to me the passage of time, a kind of obfuscation of the truth that can lead the viewer into an image as seen through the ages. What the viewer sees in my images is really up to him/her. Most people read or get a different message from my pieces of work. I like the subjectivity of that. For what they are doing is making realities of their own and possibly myths for others.

VS: There are also several references in your works to mythical tales and lore. Through your art, these often attain a personal undertone where you are the subject who is altering an accepted tale or belief to make it your reality. Could you elaborate on this?

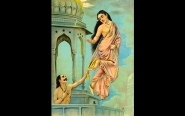

TM: This is best illustrated in “Leda’s Reprisal”. This work is based on the famous mythological story “Leda and the swan”. In the original, the King of the Greek gods, Zeus, comes to a woman named Leda in the form of a swan. The story is explicit about how he overpowers and rapes her. This forced consummation between a god and a fragile human woman results in the birth of Helen of Troy.

Looking at this story in today’s day and age, the tables are turned with the once-fragile mortal now having the god-like power and the magnificent god flying captive behind her on a loosely-held leash. The dress she is wearing is a wedding dress, which, to me, gives the image a certain further piquancy. The ease with which she holds that leash and the tameness of the swan, makes you wonder if the captivity is, in fact, forced or voluntary. Has she, the seductress, the temptress, the enigma behind the mask, turned a god to willingly live in the form of a lowly animal?

VS: You talk about expressing “beauty best through feeling, perception and intuition”. Could you elaborate?

TM: The process of my work plays an important part in elaborating on this statement. I often start with nothing in mind but a photograph that I took that fascinated me, an object caught in time that has a story to tell that is, as yet, untold. I then build upon this object infusing other objects and layers into the image until the sum total of all the parts tells a story of its own. Usually, the theme shifts away from the original objective to give rise to a completely new meaning but at each step of the creative process, I make sure not to let my original formed thoughts into my conscious mind and limit the new story that is forming in an inner conscious; which in turn becomes another reality.

Dryads in Greek mythology are tree nymphs and were very much overshadowed by the divine figures in poetry and cult. When I photographed this particular baobab tree I could make out the face and the ‘nymph’ in it, which is when my work Dryad evolved. My challenge lay in giving it a background that would bring out its inherent human qualities, while enhancing the mythical proportions of the very nature of the tree. So I have to kind of anti-instinctually, not let reason overwhelm my inner perceptions.

VS: If you were the nymph in the tree, what would your tale be?

TM: There wouldn’t be one tale: there would be several. I would be god-like, wise through having lived through the ages; seen as much as I have; witnessed what I have seen. I would hold answers to questions that nobody has even asked; know details of history that nobody knows exists; be able to recall facts that nobody has ever recorded. There is a feeling in the image of the gravity of my years, of the weight that I bear when I hold up my branches, the weight of the world that I carry (almost like Atlas). What would my tale as the nymph in the tree be? It would take too many years to answer that!

Veeranganakumari Solanki is a curator based in Mumbai.

Tanya Mehta was born in 1988 and is based in Bangalore.

Editor's Note.

Mythological Art and the Creation of Sacred Narratives

As a child, I was told stories such "lying down and eating will make your food go into the donkey's stomach" or "if you swallow a watermelon seed, a watermelon tree will grow inside you". There I was, sitting upright, imagining a miniature donkey drool in hunger.

Read MoreAs a child, I was told stories such "lying down and eating will make your food go into the donkey's stomach" or "if you swallow a watermelon seed, a watermelon tree will grow inside you". There I was, sitting upright, imagining a miniature donkey drool in hunger.

Also in this issue

Illusion: Seeing Beyond Seeing

Meaning: In Search of Significance.

Melody: A Different Tune

Rhythm: Ordering Time